I think it was a bad move,” says designer Jeremy Scott in a grave tone. “The cargo trousers and vest are a very sterile combination – he should have stayed classic.”

Scott, new creative director of the Italian house of Moschino, 39-year-old esteemed member of the fashion industry and go-to costumier for the pop world’s elite, is discussing the unsuccessful makeover of a cultural icon. “I wish they’d called me,” he says sadly. “That would have been a savvy PR move.”

The style transformation under discussion is that of Ronald McDonald, the clown who’s acted as mascot for the world’s most popular burger chain since 1963. In April this year he gave up his traditional costume (created by performer Coco the Clown in 1966) for a more utilitarian uniform. This is not a fashion move you could discuss with many designers – it’s hard to imagine Miuccia Prada giving two hoots – but Jeremy Scott has a vested interest.

In February at his debut Moschino show in Milan, he kept the audience waiting for an hour before sending out a collection about fast food and fast fashion. There were sweaters emblazoned with morphed McDonald’s arches, bags that looked like Happy Meal boxes and a dress patterned with a Fritos crisp bag. It really annoyed a lot of people. Some newspapers reported that McDonald’s employees felt humiliated by the collection. Others ruminated on the perils of glamourising fast food. One report even began by saying that while the Moschino show unfolded Kiev was burning (the show was held as the Ukrainian revolution started).

Despite this, the capsule range of 10 items from the show which went on sale the next day instantly sold out (the full collection launches this month). The designs have already been worn by Katy Perry, Beyoncé and Miley Cyrus. It’s fair to say that he started at Moschino not with a whimper but a bang.

“McDonald’s is part of our everyday lives,” says Scott when we meet for breakfast at Claridges in London four months later. “When I design I always pull from things that are significant to me. In my work I search for happiness and then try to convey that joy in the clothes.”

An answer which doesn’t explain if he was making fun of the poor who wear these clothes toiling in the fast-food industry or the rich who pay to wear his luxe versions of them. When we eat together he orders a six-egg-white omelette with spinach because he’s a devout vegetarian, so I can’t imagine that he orders many Big Macs. But that doesn’t mean that Scott is wrong or even insincere to riff on junk food in his collection. It is a part of everyday life. He says he doesn’t like to over-analyse things. Fair enough: there are plenty of fashion editors happy to do that for him.

“I’m not anti-intellectual, but primarily I try to feel things. Emotions aren’t always rational; it’s not possible to put them into words.”

Being led by his feelings has worked well for Scott. Though his name might not trip off the tongue as easily as, say, Alexander McQueen or John Galliano, he burst on to the 90s fashion scene around the same time as these designers and quickly established himself as one of the terriblest of the era’s enfants.

He was raised in Missouri, the youngest of three children, with a civil engineer and a teacher for parents. He says he always knew he wanted to be part of fashion. “I was enthralled by it. That was where I wanted to be, in the pages of fashion magazines.” He trained at the Pratt School of Design in New York and then booked a flight to Paris as soon as he graduated in 1996. Like many of Scott’s decisions, this was part grand design, part impulse. Though he’d had French lessons since he was 14 – because he was determined to make it in fashion’s capital – he had no firm plan. But soon after he arrived he bumped into a PR for Jean Paul Gaultier in the street who liked his hair (an asymmetric mohawk he’d styled himself, he’s cut his own hair since he was five) and who introduced him to all the right people.

He got a job promoting parties at the Folies Pigalle nightclub and quickly became a face on the Paris scene. His first fashion collection came in 1997. Held in a bar near the Bastille, it was themed around car crashes. Models wore paper hospital gowns and shoe heels bandaged to their feet.

His reputation grew with each collection. He sent bin-bag dresses, four-armed jumpers and wonky heels down the catwalk. Scott closed one show by throwing fake banknotes with his face printed on them into the audience. In case anyone failed to get the message, at the close of another show, he shouted: “Vive l’avant garde!”, and left yellow T-shirts stamped with the message on every seat. His work was equally praised and hated, but whatever your opinion he became a superstar. Devoted fans followed him down the boulevards when he walked through Paris; he was always on TV. Karl Lagerfeld told Le Monde that Scott was the only designer who could replace him at Chanel.

Then in 2001 he announced that he was quitting Paris for Los Angeles. At the time that was like turning down Glastonbury to play Guildford summer festival. Even his admirers were annoyed. “It was the hardest decision I ever had to make in my life because it didn’t make sense. I remember when I told Anna Wintour, she said: ‘You mean New York.’ Well, the word LA just came out of my mouth, so… Her face just scrunched and she said: ‘Why?’ I feel vindicated today: the city has become so important for fashion. That’s why I should follow my instincts.”

Does he ever miss Paris and the adoration he basked in there?

“Never. Not at all. I still go there every six months for work anyway, so I get to have a nice croissant. They’re very good at croissants.”

So while John Galliano was lauded at Dior and Alexander McQueen turned his label into an international brand through a deal with fashion conglomerate Kering, on the path that most promising designers in the 90s followed, Scott did his own thing.

He cemented his reputation as a cult label with a hardcore, fervid following of fans, particularly in Asia (“I’ve met people with my prints tattooed on them, my face tattooed on them – I have that commitment and love”). He set up lucrative deals with brands, such as Swatch and Adidas. His Jeremy Scott for Adidas range has been a sell-out hit since 2008.

He also established the relationship with the entertainment industry that had in part prompted the LA move. You may not know Scott’s name, but you do know his designs. Britney Spears’s air hostess outfit in the “Toxic” video is his. Lady Gaga’s outfit in “Paparazzi”. Rihanna, Beyoncé and Katy Perry are long-term friends and fans. Look at Scott’s Instagram and you’ll see photos of him clubbing with Rihanna or dining with Perry. He was Miley Cyrus’s date to last month’s MTV Video Awards and she unveiled her first art exhibition at the Jeremy Scott fashion show this week. “I have a way of synthesising [pop stars] message,” says Scott. “I help them do their job better and that helps my job. I understand the language of pop culture, and these people are totems of pop culture.”

So it was a surprise when it was announced last November that Jeremy Scott would become Moschino’s creative director. The superficial fit is obvious: the label, founded in 1983 by Franco Moschino, has a similarly irreverent approach. Its big hits include a jacket with “waist of money” embroidered on the waistband and smiley-face biker jackets. Like Scott, Moschino saw fashion as a form of protest. But unlike Scott’s label, Moschino’s is a brand owned by a parent company, the Aeffe Group. The name comes with subsidiary lines such as the Cheap and Chic line, jeans, childrenswear, perfume and even a hotel in Milan. In terms of business, it’s everything that Scott has avoided. This isn’t a move he’s made lightly. “I needed to feel that I could carry on being fiercely independent within the brand, that I’d have parole to do that. I feel I have it. I’ve felt it even more so since I’ve started work there. It’s exciting that there’s an infrastructure that allows me to design something in such a large amount that it could actually make a cultural difference.”

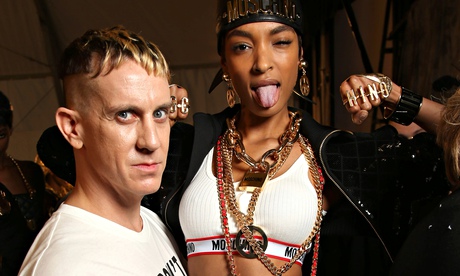

Scott is obviously ambitious, as keen to succeed in fashion as when he was a kid in Missouri or a young designer in Paris. But his Moschino debut showed that at the same time he still can’t help but stick his tongue out at the industry he loves.

As a well-educated man who learnt his trade at one of New York’s traditional colleges, who has worked for nearly 20 years in fashion, doesn’t he ever get the urge to even pretend to toe the line with the industry’s expectations? To say that his collections have loftier inspirations than, say, McDonald’s?

“No one’s ever posed that question before,” he says. “I’m stumped in a wonderful way. Chapeau.” He mimes doffing a cap. “I don’t know the answer, actually. I honestly don’t know how to do things differently. I would love to know how other designers work. There is a lot of thought behind my designs, there are bigger ideas there, but I just don’t tell people that.

“Funnily enough, though, I don’t always know when criticism is coming. I don’t know why people get bent out of shape by what I do. I mean, there are many things in the world that aren’t for me. In large part it’s water off a duck’s back though. I get love from fans in a big enough dosage that it acts as a shield, and I would not sacrifice that love in order to please the industry.”

Which is probably why he’s happy to moan about the business of fashion, even though he’s more a part of it than ever. He despairs of the homogeneity of the global industry now that conglomerates, such as LVMH and Kering, dominate. “When I started out there were individual fashion houses. Now it’s like the Montagues and Capulets, these warring factions. The beauty used to be that there were so many personalities and styles. When Vogue used to run the seasonal feature The 10 Collections That Matter, they would be uniquely different. Now it all feels the same.”

Knowing what he does about the business, if there was a kid in Missouri dreaming about making it in fashion today, would he tell him to go for it? Scott thinks for a minute. “Yes. And I would hope that I’d be an emblem for that kid.”

It’s safe to say he probably is. Vive l’avant garde!