Has culture ever recovered from the fall of the Berlin Wall? Seriously. The division of Berlin and state surveillance endured by people trapped in the eastern half of the city was the most visible and symbolic anguish of the cold war. The end of the Wall in 1989 was a sunny day for humanity. But in its monstrous strangeness, this scar running through a city had provided artists, novelists, musicians and film-makers with a dark subject matter and surreal inspiration so often lacking in the safe, consumerist world of the postwar democracies.

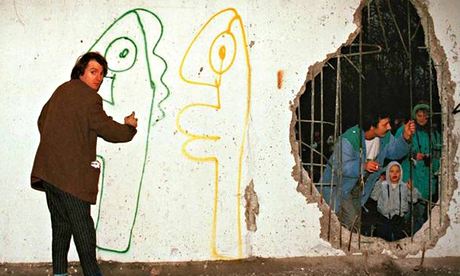

A retrospective of work by the graffiti artist Thierry Noir that opens on 4 April at the Howard Griffin Gallery in Shoreditch, east London, transports the visitor back to Berlin in the last days of the Wall. In the 1980s, Noir became the first artist to daub the long, bleak expanse of the Wall, starting a movement that is today one of the most famous things about the structure. His blocky cartoon paintings have become part of the mythology of the Wall, and appear in the Wim Wenders film Wings of Desire.

Part of the Berlin Wall is recreated in his gallery show to try to bring to life that moment in the 80s when cracks were appearing in the edifice of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, and artists, led by Thierry Noir, were comically transforming the ugly symbol of the Cold War that ran through Berlin with a carnival of bright colours and visual gags.

But the Wall's demise was the end of that artistic outpouring – literally, as large chunks of Wall covered with Noir's paintings were sold off and smaller fragments (or fakes) became souvenirs – like the one I have at home. The art of the Berlin Wall has all but vanished, along with the symbol of oppression it mocked.

Other art forms, too, have Wall-shaped holes. Where can today's brooding musicians go to find inspiration that compares with the sinister, decadent 1970s west Berlin visited by Lou Reed and David Bowie?

The Wall froze time. It prevented Berlin from becoming a neat post-war city, kept it semi-ruined and shadowed by its past as well as present. Reed's album Berlin mooches musically in an atmosphere of nightclubs and self-destruction that echoes the older Berlin of the Weimar era as much as the 70s melancholy he experienced. Similarly, such cold-war novels as Funeral in Berlin and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold are set in a city of ghosts and nightmares, a dangerous and fascinating furrow in time.

This Dada metropolis had a final explosion of black magic after the Wall came down. The eastern part of the city, suddenly opened, was revealed as a collage of urban utopias and terrors where the concrete visions of communism mingled with walls still bullet-riddled from 1945. It became an anarchist playground. Meanwhile, the no-,man's land left by the Wall's destruction was a raw archaeological zone where surviving bits of graffiti stood beside Nazi bunkers.

This fantastic shadowland quickly got turned into a shiny, happy city, fit to be the new Germany's capital, with expensive, flashy and often very exciting architecture rising up.

Art flourishes in 21st-century Berlin, but does it matter as much as it did when the city was a cold-war danger zone? Thierry Noir reminds us of Berlin's faded lipstick traces of dissent.