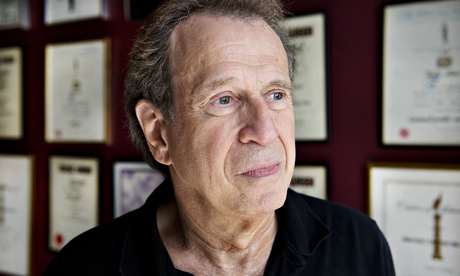

In the mid-1970s, Nicky Chinn, one half of the Chinnichap songwriting team along with Mike Chapman, purveyors of hits to Sweet, Mud, Suzi Quatro and many others, was asked what was his musical ambition. “I said I wanted to write a standard,” he now recalls. “It was a flippant thing to say in a way, because in reality we weren’t focussed on anything much beyond that week’s chart. But in another way I meant it, although I admit I didn’t envisage that the work we were doing then would have the sort of longevity I associated with songs like Three Coins in the Fountain.”

Indeed, a lyric such as “That’s neat, that’s neat, that’s neat, that’s neat / I really love your tiger feet”, is not obviously in the tradition of Sammy Cahn, but, 40 years on, Mud’s hit can still fill a wedding dancefloor. Chinnichap’s songs proved hugely successful vehicles for Quatro’s teen tomboy rebellion (Can the Can, 48 Crash and Devil Gate Drive), Mud’s working men’s club-meets-panto version of 50s rock’n’roll (The Cat Crept In, Lonely This Christmas as well as Tiger Feet ) and the glammed up hard rock of Sweet (Ballroom Blitz, Teenage Rampage and Blockbuster). And these are just some of the hits from 1973 and 1974 alone. Music from the whole Chinnichap catalogue – including later songs for artists as disparate as Tina Turner and Toni Basil – now gets the jukebox musical treatment in a new show, Blockbuster, with Paul Nicholas starring in a story about a Soho busker who time travels back to 1975.

“Of course our primary motivation was to sell as many records as possible,” explains Chinn. “But we also worked very hard on making them good. I don’t think any of our hits were bad songs, and, as someone who grew up with pop music and never fell out of love with it, it is very pleasing to see that they were not only popular, but also durable.”

Chinn, born in 1945, says that from the beginning he was attracted to a pop sensibility ahead of any notions of credibility, cool or the importance of the artist. “I really liked Dylan’s early stuff, but when buying his records I’d also buy a Gerry and the Pacemakers song at the same time. Later I got into James Taylor and Crosby Stills and Nash, but still bought Herman’s Hermits records.”

From a well-to-do family, he had escaped the family car business and got his break as a songwriter when Mike D’Abo – the Manfred Mann singer and composer of Handbags and Gladrags – saw some of Chinn’s lyrics via a girlfriend and included two of them in his score for the 1970 Peter Sellers and Goldie Hawn film, There’s a Girl in My Soup. A few months later Chinn met Mike Chapman, an Australian musician in a band called Tangerine Peel making ends meet as a waiter in Tramp nightclub in Mayfair. They talked music, arranged to meet up and wrote four songs in a day. “They weren’t very good songs,” says Chinn, “but at the same time they weren’t abysmal, and most importantly they showed there was some chemistry between us.”

After a period of unsuccessfully hawking their music round London publishers – “Tin Pan Alley as a venue had just about disappeared by then, but that way of doing business had not” – they eventually contrived a meeting with producer Mickie Most, who rejected four of their songs halfway through the first chorus, “which actually makes sense, because it isn’t going to get better after that,” says Chinn.

Most then stopped a fifth song at the same point, but this time declared it a hit. “Tom Tom Turnaround” was given to the group New World and duly made it to No 6 in the charts.

Around the same time, Chinnichap became involved with Sweet, a capable heavy-rock band who were persuaded to try their luck first with a bubblegum single – “Funny Funny” – before buying into the glam predilection for makeup, but without the Bowie or Bolan-esque androgyny. Sweet’s stubble-and-mascara look suggested more a bunch of leery blokes after a few pints who had had messed around with their sisters’ make-up bag. But they provided Chinnichap with their first No 1 when Blockbuster held off Bowie’s The Jean Genie – which shared a remarkably similar guitar riff – in January 1973.

Other number ones from Quatro and Mud soon followed and, Chinn says, the seemingly unstoppable run of success began to be accompanied by a certain arrogance. “It was an industry where you could go to bed on a Monday night and no one had heard of you, and by Tuesday lunchtime, when the charts were released, everyone wanted to copy you. It was tough to deal with, and even today I’m not sure I would be able to advise anybody how to handle it. We did the expensive cars, the clubbing, the drinking too much and maybe not treating people as nicely as you should. For a time we thought we were God’s gift to the music business, because for a while all the evidence said that we were.”

An acrimonious split with Sweet came after the band recorded one of their own songs for a single without telling Chinnichap. “They became frustrated and wanted to be their own masters,” says Chinn. “And Fox on the Run was a great song as was the next one. Then that was it for them. We’ll never know, but they might have been better off staying where they were. But part of it was that they were very, very good.

“Mud were nicer guys and easier to work with, but maybe they didn’t have quite the same talent.” And just as the pop hits began to peter out, Chinnichap were also confronted by the arrival of punk: “I was not enamoured, but I did smile when lots of the people on the punk scene were absorbed by the record industry and pretty quickly became the epitome of everything that they had hated.”

By this time Chinnichap were providing global soft-rock hits to the likes of Smokie (Living Next Door to Alice) and Chapman had moved to Los Angeles. Chinn followed him in 1979, buying Paul Newman’s old house. Songs came for Huey Lewis and Tina Turner, but their major success was Toni Basil’s Mickey, “our only truly multi-generational song and one that has never gone away, cropping up in commercials and movies and odd things all over the place”.

By 1983 the partnership was over. Chinn says it was a casualty of the intensity of their working relationship “and perhaps of the hedonistic lifestyle of LA. We’d got carried away with it all. We had a record company that failed. We never should have had a record company, and we weren’t used to failure, but we thought we could do anything. It was all tremendously painful. It was like a divorce.”

Chapman went on to carve a career as a successful producer, most notably of Blondie, and Chinn came back to London and worked with one or two other people, but “there was no way I was going to recapture that chemistry, and for a long time I didn’t really feel like working at all”. It is only in the last eight or nine years that he started writing again, most often in Nashville where he has written songs for Westlife and Donny and Marie Osmond.

“I love working there, but for me it is not as crafted as the way I used to do it with Mike. In Nashville they want to write a song in a day and they will write a song in a day. I sometimes find myself saying it’s not quite good enough, we’re not finished. Mike and I did have a tremendous work ethic and we would keep going at a song until it was the very best it could be. I think we were far more fussy than they are in Nashville today.”

And when the Blockbuster musical was proposed, it was those fussily produced songs that brought Chinn and Chapman back to the same room, and got them speaking to each other for the first time in 25 years at an early run-through. “It really was all our yesterdays hearing the songs and seeing each other at the same time. And it was such a different experience to hearing them on the radio or seeing them on television.

“They had to survive on their own two feet, aside from the performances that made them famous. It was a mind blowing experience. Mike and I were absolutely thrilled. What do you call songs that have lasted this long? Standards?”

• Blockbuster is at the Orchard theatre, Dartford until 20 September. Then touring.