As I return to New York City from a summer in Europe, two days before the 12th anniversary of 9/11, I glance up to see the Tribute in Light – two ghostly, beautifully impossible shafts of light representing the World Trade Centre towers. Before these shafts of light stands the now single-finger gesture of the Freedom Tower, dominating the skyline just as the Twin Towers did. A sliver of new moon floats nearby. The relevance of these symbols brings me, well, back home. I’ve lived in NYC since 1987, 1993 or 1997, depending on which government agency you ask.

On the morning of 9/11, I was asleep in my apartment on Jane Street in the Meatpacking District, just north of Ground Zero. I received a phone call saying New York was under a terrorist attack and that I needed to leave as soon as possible. I sat up in bed and heard the sirens outside my bedroom window. I looked down at my naked legs, and said out loud, “Oh fuck.” My notion of home had suddenly changed. But what is home, anyway? Cue the Gang of Four song, At Home He’s A Tourist. I’ve felt that way about everywhere I’ve lived since the age of seven, when I first moved from the States to Frankfurt, Germany, with my military father and family. My life has been nomadic by both necessity and choice. I’ve looked at my homes as “bases” –places I return to when I’m away from a home-like base. I know that sounds Arthur C Clarke, but it’s true.

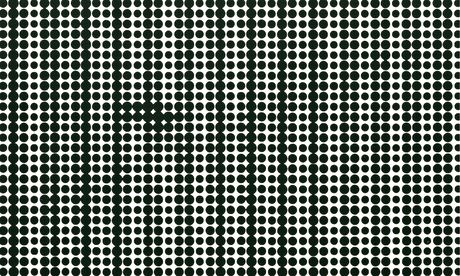

Where do we locate home inside ourselves? What images go so incredibly deep that, like it or not, they define our world, our inescapable home? With a small, powerful set of images, Douglas Coupland actually manages to playfully (how did he pull that off?) remind us of our collective 9/11 moment – the act that unzippered the 21st century in most of the world, and changed my notion of home and safety forever. Coupland’s at first seemingly Op Art paintings are just black dots – abstract, weirdly familiar. But then you look at them on your iPhone (because you’re going to take a pic and post it … this is 2014, after all) and you have the ahhhhhhh moment when a chill runs down your spine and you realise that it’s them: the jumpers. It’s him: the boogeyman. Doug offers us the choice to either see or not see these deeply internalised images. Having that choice is what enables us to survive from day to day without going nuts.

His images also remind me that nobody really knows how to look downtown any more without feeling, in some way, conflicted. Every time I see the Freedom Tower, I think of “freedom fries” – the term coined when the US wanted to invade Iraq, and France objected. Anything attached to the word “French” in the US was then relabelled with the word “freedom”: freedom toast, freedom fries, freedom kiss, for fuck’s sake. French wine was banned, French people were spat upon, their heads in photographs replaced with heads of weasels. Forget the Statue of Liberty and where it came from. It was a disastrous response—a horrid turn on the formerly leftist act of boycotting as protest. I’ve never been more embarrassed by my country, (except when we re-elected George W Bush and Dick Cheney). I largely blame the media for this egregious abuse of power and influence.

The Freedom Tower was meant to inspire patriotism and instead embodies the darker sides of nationalism. The 9/11 attacks and the Bush administration’s response, buoyed by the media, and our shock at having finally been direct victims of terrorism, paved the way for a whole new take on “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” There was no longer any need to explain or publicly debate militaristic power, or the police state mindset. To do so was to be the opposite of a patriot.

There’s another way I look at the Twin Towers that’s perhaps more specific to myself. Every time I look at where they used to be, I try to think about New Yorkers in the 1960s and 70s who were horrified when they were built. The towers that were going up must have destroyed not just the skyline but, in their minds, also what the downtown stood for. So, I guess, historically speaking, I feel sad about the towers being there in the first place, although architecturally they were pleasant enough to look at from my late-70s forward perspective. And if nothing else, the Twin Towers helped the direction-impaired (me) know which way was north and south. And there were some great, wild dance parties at the rooftop restaurant. It was a moment and that moment is gone. But I am being nostalgic here and romantic.

Someone asked me, “Do you think children born after, say, 1994, will ever feel the same things about 9/11 that people born before then feel?” More and more, what we “feel” about collective history seems like something manufactured, and kind of pumped into us, rather than a real emotion. It’s all so framed by the sense that reality doesn’t exist any more, or at least not in a way that is alterable or questioning. Coupland’s images of jumpers and of the ultimate boogeyman, Bin Laden, remind us of how deep inside us those images are lodged, how they can never be removed, and how, as time passes, their meanings remain as potent as ever, even though we can’t fully decode them. By evoking memories that can’t be deleted by wilful ignorance or overabstraction, Coupland reminds us that we all share a set of uncloseable doors in our minds, and through these opened doors, in an almost cartoon-like way, now march the NSA, Google, spooks, shadow governments, a lost, pathetic fourth estate, squandered militaristic might and rampant, terrifying nationalism. And while this procession occurs, we seem to be shrugging our shoulders and saying, “Eh, I’m still here! And I’m OK!! Let’s just get on with it!!!”

Support our troops!

Oh no … really? Is that who we are now? Blind, unquestioning, warlike? Are we that violent, that childish, that silly, that shallow? Are we that afraid of others? Of ourselves? Of the possibility of genuine change? Are we that easily swayed, that capable of defending “American interests”, whatever “American interests” means? Are we that racist, that terrified, that protective of an idea that we don’t even question what the idea has come to represent?

Never forget!

Well, hold on. In some ways we don’t need to remember any more: it’s all being stored, for however long forever is, in our external hard drives. We’ve uploaded ourselves on to the Cloud, always there to look at, reference, recollect or ignore. In one of Coupland’s works, called Boogeyman in the Sky with Diamonds – the black-on-black image coated with stars – Bin Laden is barely there, but he’s totally there. Coupland has given him a now-you-see-him-now-you-don’t face.

God bless America.

In my mind I’m seeing unblinking eyes: HAL 9000 surveying Dave the astronaut; I’m seeing Doug Coupland surveying the 21st-century world; I’m seeing video surveillance everywhere. I’m seeing ourselves watching ourselves and it’s deeply frightening, as a new form of infrastructure that relentlessly monitors and peels back our privacy, our mysteriousness, our individuality, in every way. Do we all need to feel like we’re living in a movie, thousands of unseen cameras invisibly choreographing scenes with our words, our actions, our movements? And are we almost to the point, thanks to the internet, of providing ourselves with our own laugh track? The googly eyes on Coupland’s Osamas lead me to think that one day we will.

Incredible.

In sha’Allah. Allah willing.

• Thoughts on the 21st Century, taken from Douglas Coupland’s Everywhere is Anywhere is Anything is Everything (Blackdog Publishing).