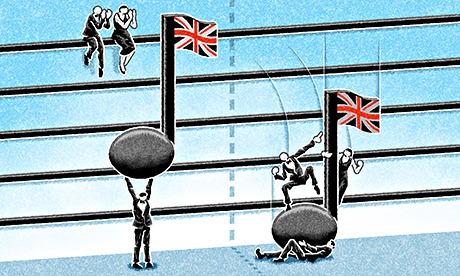

In a piece of timing so excruciating it will have Alex Salmond rubbing his hands in glee, this Saturday the BBC will broadcast the annual flag-waving Brit-fest that is the Last Night of the Proms. It would be hard to think of a moment when Britain’s long lazy reluctance to take a critical look at itself in the mirror seems more particularly wilful and inappropriate. Yet Scotland is not the only reason why this is so.

Sir Edgar Speyer has an important part in Proms history. Today he is a forgotten figure. A century ago, however, he was the most high-profile victim of a dubious and vindictive legal process with strong contemporary echoes and resonances: what the veteran human rights lawyer Sir Louis Blom-Cooper says was the result of “an unyielding prejudice against a distinguished man”.

Speyer was born in 1862. A member of a banking family, he became an immensely rich Edwardian financier and philanthropist who, in 1909, was made a member of the privy council by his friend Herbert Asquith, the Liberal prime minister. When Asquith threatened to flood the House of Lords with Liberal appointees in 1910, Speyer’s name was on the list of likely nominees.

At the time, Speyer’s greatest claim to fame was the use to which he put his money. At the top of this list of investments was the Edwardian-era expansion of the London Underground, in which Speyer was the principal backer for the electrification of the Metropolitan and District lines, and the construction of what became the Bakerloo, Northern and Piccadilly lines.

But Speyer was also a major philanthropist. He was a big donor to the King Edward VII hospital and to University College London. And in 1911 he was the main guarantor of Captain Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the South Pole. One of Scott’s last letters, found with his body in Antarctica, was to Speyer, thanking him for his generosity and promising: “We shall die like gentlemen.”

Speyer’s greatest private passion, however, was music. His American-born wife, Leonora, was an outstanding violinist. Elgar, Grieg and Richard Strauss were among the composers who dined with the Speyers at their Mayfair house, where a portrait of Leonora by John Singer Sargent hung in the music room. Strauss dedicated his opera Salome to Speyer in 1907. And in 1902 Speyer stepped in to save the Proms after their founder, Robert Newman, went bankrupt. Speyer continued to underwrite the Proms for 12 years.

In 1914, however, everything turned. The Speyer family was German. Speyer himself had been born in New York and came to this country in 1887; he was naturalised as a British subject in 1892. But his family were Frankfurt Jews, and Edgar Speyer ran their London banking house while his relatives ran those in New York and Frankfurt. When war broke out in 1914 Speyer continued his financial and family contacts with Germany until they were prohibited. Yet even then, the Speyer financial house in the US continued to deal with Germany (until 1917 the US was not at war).

Some of Speyer’s behaviour in those early wartime months was undoubtedly ill-advised and even, on some counts, illegal. But there is no suggestion that Speyer was pro-German in the conflict. Even so, in 1915 he was forced to flee to the US because of anti-German feeling. Then, two years after the war, his British citizenship was removed and his privy council membership struck down following a tribunal, when the home secretary, Edward Shortt, ruled that Speyer had been “disaffected and disloyal”.

Today, according to Blom-Cooper’s foreword to Antony Lentin’s book on the Speyer case – evocatively titled Banker, Traitor, Scapegoat, Spy? – such a process and verdict would have been impossible, a breach of human rights. Even during the war, many took Speyer’s side, including Asquith himself, who refused Speyer’s 1915 offer to resign from the privy council with a dismissal of “these baseless and malignant imputations upon your loyalty to the British crown”.

At the time of the 1921 tribunal, the Manchester Guardian also reported that Speyer had many friends (including George Bernard Shaw) who “will entirely refuse to believe that he has been guilty of the charges laid against him”. When Speyer died in 1932, his Guardian obituary concluded that he was “the object of attack by those who sought during the war years to drive out of the country or have interned every resident of German parentage”.

Few now realise it was Speyer’s money that made sure “the world’s greatest musical festival”, the Proms, exists to this day. A century on from the first world war, few know either that Speyer was the principal victim of wartime anti-German hysteria. And, at a time when David Cameron is trying to make it much easier to deprive British jihadis of their statehood, few remember that Speyer was one of the very first Britons to be stripped of their nationality in a manner marked as much by prejudice as by proper legal process.

This year the Proms have focused many concerts on music of the first world war, almost all by British composers. On Saturday, as they sing Parry’s Jerusalem and Elgar’s Land of Hope and Glory, few in the audience will be aware that both the Liberal Parry and the Conservative Elgar supported Speyer against those who waved union jacks, and worse, in his face a century ago. Is it too much to ask that someone in the hall – perhaps the evening’s conductor, Sakari Oramo, in his traditional end-of-season speech – will spare a thought for the Proms benefactor who was treated so vindictively by the pig-headed jingoism of an earlier age?