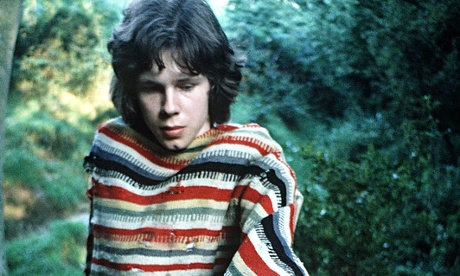

Forty years on from his death aged 26, the music of Nick Drake is still providing moments of otherworldly calm and solace, even in an environment as hectic as the Edinburgh festival.

Having been an art exhibition and a book, Michael Burdett’s Strange Face project is now a spoken-word show, which takes place in the back room of Edinburgh’s horror-themed Jekyll and Hyde pub. It tells the story of an 18-month period, from 2009 to 2011, in which Burdett visited every county of mainland Britain, asking random strangers to listen to an unreleased version of Drake’s Cello Song, and then photographing them as the music percolated through the headphones.

“I could never tell how people were going to respond,” says Burdett. “I photographed them laughing, crying, lost in the moment. If you look at the picture of Ross Noble, it’s like a man looking inwards.”

Burdett was first exposed to Drake’s music aged 11 on the John Peel radio show. Though he is now regarded as a lost genius, Drake barely sold any records when he was alive. Bryter Layter, the most popular of his three albums, is estimated to have sold around 3,000 copies on its release. The February after his overdose on antidepressants, judged by the coroner to be suicide, the NME’s Nick Kent wrote an article about the singer’s life and work, which marked the beginning of Drake’s ascent to the pantheon of cult heroes. Today, he is revered by famous fans from Kate Bush to Brad Pitt, who hosted a recent radio documentary about the singer.

Burdett describes Drake’s music as “bleak, extraordinary and timeless”. He had found the tape in a skip at Island records back in 1979, where he was working as the postboy’s assistant, attracted by what appeared to be Drake’s writing on the sleeve. Today Burdett writes music for TV: his compositions include the themes to Masterchef and Homes Under the Hammer. So does he get a royalty every time they’re played? “None of your business!”

Burdett also makes his own music under the name Little Death Orchestra. He was trying to finish a complicated piece when in a fit of what he describes as “displacement activity” he decided, for the first time ever, to play the old tape. It turned out to be a very different version of Cello Song to the one on Drake’s first album Five Leaves Left: “The percussion was funkier, the cellos played more aggressively, and Drake’s voice was beautifully recorded but ever so slightly different.”

The Drake estate controls the singer’s unreleased recordings and are currently embroiled in a dispute about another demo tape, though they recently allowed an early John Peel session, including a different version of Cello Song, to be rereleased – you can hear it here. “They look after his legacy in a really responsible fashion – they treat him like he’s a living artist,” says Burdett. “He’s not here to make decisions [about releasing outtakes] and I’m sure they would argue that there’s a perfectly good version of Cello Song out there already.”

Burdett knew that broadcasting his tape of Cello Song would breach the Drake estate’s copyright: he doesn’t play it in the Edinburgh show. While he was keen to share the tune with other fans, “I didn’t want to be known as a bloke who had this recording and just shared it with his mates.” It was when watching the Werner Herzog documentary Grizzly Man, which includes a section in which the director listens to a recording of his subject being eaten by a bear, that Burdett hit on the idea of playing a selection of strangers something that would bring them pleasure instead of horror – his Drake recording.

He had little photographic experience. “My friends used to laugh whenever I picked up a camera because my photos would invariably have heads missing,” he says. “I’m a genuinely terrible photographer, but with a good camera and four minutes and 22 seconds of someone distracted I could guarantee getting one shot that looked like I really know what I’m doing.”

Though the project was intended to be random, it has a high celebrity count, ranging from Fearne Cotton to Jeremy Clarkson, who described Cello Song as “really bloody good”. “I work in television and I come out of the studio and there would be Martin Freeman or Charlie Higson,” explains Burdett. “If Tom Stoppard is walking towards you and in your rucksack you have a lost Nick Drake recording, of course you want to know what he’s going to say.”

However, Burdett points out that he also photographed “tattoo artists, mountaineers, city workers, homeless people, florists, doctors …” Of the 200 he approached, 167 agreed to be photographed – and only two said that they didn’t like the song. “A Chelsea pensioner called it dirgey, and a motor mechanic said it was depressing,” says Burdett. “The rest said things ranging from ‘that’s nice’ to ‘this is the best moment of my life’. I bet even a new Beatles recording wouldn’t have had that impact.”

Burdett explains in the show a few uncanny coincidences that he came across on the road, not least an unnerving encounter with a past life regression therapist in which the ghost of Drake seemed to loom out of the mist which suddenly descended as she listened to the song. (The ghost turned out to be a vision of a boy on a hoverboard.)

He also approached a man who turned out to have been one of Drake’s friends, an artist called Adrian George who used to work for Joe Boyd, Drake’s producer. “He said they all used to hang out at a flat in Ladroke Grove,” says Burdett. “Nick would invariably be in the corner, stoned, and everybody who came to the house thought he was the sweetest guy. Occasionally he would make up the numbers playing poker dice – he said he [Drake] wasn’t the most natural poker dice player in the world. I asked what he thought about Nick Drake’s music and he said “oh, he played music as well? We spent our lives in a Baudelairian haze.’”

In the course of this, his first ever one-man show, Burdett says that he has discovered that his real subject is not Drake but the way that music can be a conduit for emotional closeness, even between strangers. As they were disarmed by Drake’s moving music and his sad story, they started opening up to Burdett.

“People talked about more than music – they talked about their lives, their loves, their losses, their ambitions,” he says. “If I could wander round Britiain for the rest of time stopping random strangers and taking photographs as they listen to this extraordinary recording, I’d do it in a flash. If you ever lose faith in human nature, go round the country with a lost Nick Drake recording in a rucksack. People reveal themselves to be kind, curious, informative, interesting and wonderful.”