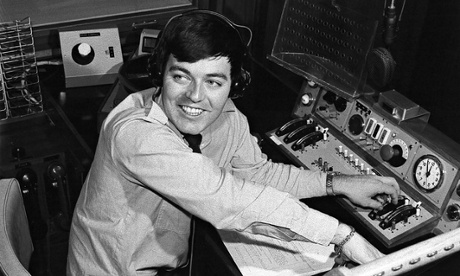

Tony Blackburn is baffled. The disc jockey has just celebrated 50 years in the business and suddenly everybody is being nice about him. For decades, the man who launched Radio 1 at 7am on 30 September 1967, with The Move’s Flowers in the Rain, was the whipping boy of the cool crowd. With his naff jokes, cheesy cheeriness, gold medallions and public breakdowns (when he and his former wife Tessa Wyatt split up, he played Chicago’s If You Leave Me Now repeatedly on his show), he became an easy target for satirists. Paul Whitehouse’s fabulously dim DJ, Dave Nice (half of Smashie and Nicey), was a tribute of sorts to Blackburn while Steve Coogan’s fatuous wally Alan Partridge bears a passing resemblance.

But nobody is laughing at him any more. Now, he is praised for his longevity, his decency, his championing of soul music, his integrity even. And he is embarrassed by all the attention. “I’ve found it a bit overwhelming, actually. The 50th anniversary thing. The BBC has been wonderful to me. I’ve had ‘Fifty at Fifty’ where I chose my favourite 50 records, then there was a programme where I had my portrait painted as I was being interviewed. Soul singers like Leee John and Jaki Graham were coming on and saying how wonderful I was ... It’s very nice, but yeah, a bit weird.”

It has been a terrible couple of years for Radio 1 legends, with a series of historic sex abuse allegations levelled against former disc jockeys. You might well be forgiven for thinking that sexual harassment (at best) was part of the job description back in the 1970s. But Blackburn has been untouched by the scandal; perhaps the one old-timer whose reputation has been enhanced in recent years. “People are beginning to realise how much I loved the music. They thought it was all jokes.”

Blackburn was equally adored and loathed in his heyday. Many considered him unduly immodest, but he insists he was sending himself up. “I’d go on stage and say: ‘I’ll stand here for a minute and let you admire me ... I wish I was out there with you, enjoying me!’ I got a lot of heckles because I was only 24, and I didn’t look the wreck I look now. Hahahaha! People thought I was serious.”

Then there was Blackburn the provocateur. When the miners went on strike in 1973, it interrupted his pantomime performance – the lights went out mid-show – so he told them to get back to work. “It probably wasn’t the best thing to say. Yes, I was reprimanded for that. I was taken off the air.” He was given a two-week ban. But it would be simplistic to pigeonhole him as a reactionary. He is also a vegetarian (he stopped eating meat at five because he liked chickens), a militant atheist, and a pacifist with a radical bent. “I believe everybody from different races should sleep with one another, and so eventually we’d have children who couldn’t be discriminated against, which would be wonderful.”

Blackburn started on the offshore pirate stations Radio Caroline and Radio London. His father, a GP, had wanted him to go to Rugby school, as he had done. But Blackburn was not academic or serious-minded – he boarded at Millfield (another public school) on a sports scholarship, captained the cricket team, left without taking O-levels and eventually passed a handful after private tuition.

Apart from a brief period as an almost-popstar, he has dedicated his career to radio. Today, his face might be somewhat sunken, his blue eyes a little shrunken, but he is still very much the popadoodledoo, Tiggerish DJ of yesteryear – small in stature, big white teeth, hyperactive, optimistic, full of laughter, often at his own appalling jokes. At his peak, Blackburn was more famous than most of the pop stars he plugged. “The Radio 1 DJs were a massive attraction. We were mobbed everywhere we went.”

He became a sex god, didn’t he?

“Me? Oh yes. YEAH!” He laughs it off.

But he boasted about all the women he slept with, I say. At one point he cited 250 women, then there were 500.

“Yes, I shouldn’t have done that.” He cringes. “That was a mistake.”

He tells me how he was writing his autobiography with the journalist Cheryl Garnsey, and she said it needed spicing up with sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. “So I did the rock’n’roll, and I said: ‘Well, I don’t do drugs.’ Then she asked me about sex, and she said: ‘How many people have you slept with?’, and I said: ‘Well, quite a few.’ And I started counting them up. I should have left it out. It wasn’t a nice thing to put in the book; not nice for my parents. What’s there to brag about?”

Why did he do it? “Well I didn’t read the autobiography before it went into print. I should have done,” he says meekly.

“That’s ridiculous. You have to read your own autobiography.”

He nods, apologetically. “I know you do. Of course you have to. I didn’t feel nice after it, and it’s haunted me ever since.”

Look, he says, he knows that is inexcusable but he is not embarrassed about the women – he does not think he did anything wrong, they were all consenting adults. “I was a single guy, I didn’t hurt anybody and there was nobody like ... all the stuff we’re having nowadays. I was working very hard, travelling all over the place doing discos and in my private life I was like any other person. I met somebody in a bar, and it just happened. It was just that sort of era.”

He pauses. “I would never have dreamt of going into an office and touching somebody up. You just don’t do that. I was always very respectful of people. I never saw Savile do anything wrong, I didn’t realise how bad he was. It has tainted that era. It’s horrible, horrible, horrible.”

Did he suspect Jimmy Savile? “There were stories that he liked younger people. Rumours. But unless you see somebody doing something wrong, you can’t report anybody. If I’d seen him doing anything I would have said something, because my view is younger people are younger people, and to me a child is sacred. All this stuff we’re hearing now is horrendous. I’ve got children, I’m a father, I can’t understand it, It’s just … euch, it’s horrible. And my only regret is Savile is not alive to take the punishment he should have done.”

Blackburn says Savile was not really part of the Radio 1 team. He went round the country doing Savile’s Travels and sent the tapes in. But they did do Top of the Pops together, and Blackburn found that a chore. “He’d always try to one-up you. If I was doing a link he’d always try to put me off. He was just … just Savile. Not pleasant.”

I ask him whether he was scared of him, and he says no. If he was not, others certainly were. “Every year people voted for their favourite DJ. It was a big deal because you compered the NME poll winner’s concert at Wembley. Jimmy Savile had always won it, and he was a great friend of the person who owned the NME [Maurice Kinn, who died in 2000]. Then, the year I opened Radio 1, my agent Harold got a phone call from the person who ran the NME at the time and he said: ‘There’s a problem – you’ve won it, but Jimmy Savile always wins it, and he wants to compere the show. Could we make Savile a joint winner with Tony Blackburn? We know you’ve won it, but go along with it because Savile is Savile.” Was that Savile’s influence? “Must have been. So we did the show between us, we jointly won the most popular DJ of the year.”

Blackburn also had run-ins with the indie king John Peel, who often made jokes at his expense. “He looked upon me as the devil for some reason.” Did it upset him? “Only when he had a go at me in the press for no reason. Whenever we met, he said: ‘People don’t realise how much you’ve done for soul music,’ and I said: ‘I bet you’d never say that publicly,’ and he said: ‘Oh no!’”

Why would Peel never admit it publicly? “I think he was jealous that in the early days I was built up as this Radio 1 thing, and he was always on in the evening. He wasn’t in the mainstream. He realised he wasn’t as good as the rest of them on top-40 radio. He was slow, his voice wasn’t right for it.”

He says Peel was a clever man who captured a niche market. “One day, he was sitting in the studio listening to this very odd music, and he said to me: ‘This is a load of shit but I could make something out of it.’ And he made this programme called The Perfumed Garden with it, which was very successful on Radio London. Eventually, he got to love the music but originally his reaction was: ‘God, this is odd.’ Then when he went to the BBC, he realised he could make a name for himself as an alternative DJ. He wasn’t stupid, he knew what he was doing. ”

Despite the spats at Radio 1, Blackburn insists he had a great time and that it bore little relationship to anything we might read about now. “In those days when you went into Radio 1 it was a beautifully run organisation. You didn’t go into an office and there were people misbehaving, you just didn’t see it. I mean, I never got groped by anybody in the 1960s ... Bit of a shame really. Hahahaha!”

In 1980, Blackburn’s career took a nosedive, and he was relegated to presenting Junior Choice. “When you go from having done the breakfast show to mid-morning to afternoon, and suddenly you find yourself doing a kids’ show at the weekend and playing Puff the Magic Dragon, you think this might be the time to call it quits.” Close your eyes, and you can occasionally hear Alan Partridge – though a rather panglossian Partridge.

Blackburn saw his fall as an opportunity to reinvent himself. He joined BBC’s Radio London and blitzed his listeners with soul and risque allusions to “12-inchers”. “I wanted to do a programme that was entertaining and fun. Soul music is sexy music, raunchy music. I didn’t want it to be a niche thing, I wanted to bring it to a mass audience. I wanted cab drivers to listen to it because I think pop soul is fabulous, I do, really. To me that is my religion. Black soul music. It is, it’s a religion. I just happen to be in a white body. Hahahaha!”

Blackburn recently won his second lifetime achievement from the Radio Academy for 50 years’ service to broadcasting. He bounced on to the stage, super-smart in dinner jacket and bow tie, delighted to be there, and announced: “I’ve not been arrested yet!’’ It was a brilliantly inappropriate comment from the grandee of popular radio, but in a way it said it all. After the horror of Savile, and the arrests of Dave Lee Travis and Paul Gambaccini following sex abuse allegations, it feels that nobody is safe.

You’re not going to let me down, and be arrested by Operation Yewtree, are you, I say. “No,” he says adamantly. “Nonononono. No, I’m not going to be arrested.” As he talks, I’m thinking how unchanged his voice is from that day he introduced “the exciting new sound of Radio 1”, with the “just for fun” jingle and imaginary dog Arnold barking in the background. (“If this one doesn’t wake you up nothing will,” he said as he launched Flowers in the Rain.) After 26 years in exile on local stations he returned to national broadcasting in 2010 to present Pick of the Pops on Radio 2. By then, he and his second wife Debbie had a teenage daughter (“She is so much brighter than either of us”), was regarded as a soul aficionado, had surprised everyone by winning I’m A Celebrity Get Me Out Of Here in 2002 (“I never knew people liked me till then”), and had lost some of his early insecurities but none of his enthusiasm.

“I can’t do anything else,” he says, “and I do really love radio. I’ve loved it from when I was an early child. I still get a lovely warm feeling going into Radio 2 on a Saturday and a sense of excitement. I love studios. I’d like to live in a studio.” He giggles with delight. “I love everything about it. It’s warm and lovely, and I just love it. I’ve always been happiest when I’ve been at the BBC.” He pauses, and you can tell he’s on the cusp of another cheesy Blackburnism. Sure enough, he doesn’t disappoint. “The BBC is the Blackburn Broadcasting Corporation for me. Hahahaha!”