Sales of music downloads may have peaked and already tipped into decline, thanks in part to the rise of a range of streaming services, from Spotify and Pandora to YouTube and SoundCloud.

In the first part of my interview with industry analyst Mark Mulligan, he discussed why this long-predicted trend has still been a shock for many people within the music industry, and suggested that streaming subscriptions are still mainly for early adopters.

What does this mean for some of the big companies in the digital music world: Apple, YouTube and Spotify? And just as importantly, what will it mean for the musicians who write and play the songs being streamed on these services?

What Apple should do next

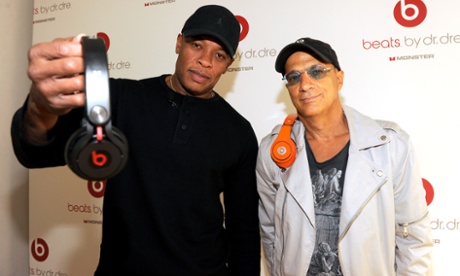

Apple is holding its next big press launch on 9 September in Cupertino, where it’s expected to unveil one (or possibly two) new iPhone models, as well as its long-anticipated wearable device. But now that the company owns streaming music service Beats Music, Mulligan thinks it could spring a surprise.

“The easiest thing they could do, if they had an appetite for it, would be to make a commitment to swallow more of the costs of a £9.99 monthly music subscription, if they’re willing to bundle it into a device,” says Mulligan.

“With those two levers that you pull to decide how big the addressable market is, if you take away price as one of those barriers, Apple will have so much more of an addressable market than the other services.”

Why would Apple bother to suck up some of the costs of a subscription music service in 2014, when it makes so much money from its non-music products – devices, obviously, but on the digital content side, apps too?

Mulligan thinks the growth of standalone music services like Spotify is a threat to Apple, because they appeal to the same kinds of people who are its most valued customers.

“iTunes was a really important part of their velvet handcuffs: people invested time and money building up big iTunes collections, which could only be easily enjoyed on iTunes-compatible devices,” he says.

“It’s one reason why people would tolerate those other things that weren’t so good: they might see a whole bunch of Samsung and HTC devices with better features and cameras, but they’d upgrade to the new iPhone anyway.”

With a Spotify subscription – complete with your personal music collection as streaming playlists rather than stored files – switching to Android gets one step easier.

“The irony is that this is coming full circle for Apple, and why it will move back towards a music-centric phone sometime. It always used music as a way to sell devices and win customers, yet now music might be a thing that may lose them customers,” says Mulligan.

We’ll see what 9 September brings on that score.

YouTube’s role in digital music

Mulligan’s latest report – The Streaming Effect: Assessing the Impact of Streaming Music Behaviour – is blunt in its portrayal of YouTube’s role in the digital music industry, and the threat that it poses to subscription services.

“34% of music streamers won’t pay for music because they get all they need for free from YouTube,” it claims, before adding that “YouTube quite simply sucks too much of the oxygen out of the competitive marketplace for premium services to compete effectively.”

YouTube is preparing to launch its own paid subscription music service, though. Mulligan thinks it faces a bigger challenge than expected in persuading people to sign up for it – but that ultimately, this may not be a big headache for the company.

“If you’ve built a business around free and attracted a user base predominantly for that reason, the vast majority won’t pay if you start trying to persuade them to. And how much can you afford to take away from ‘free’ in order to make the paid seem better, before you start losing your free audience?” he says.

Mulligan says there are “good people” within YouTube and Google who want to make a success of digital music – including getting people to pay for it, rather than just use YouTube for free – but suggests that the planned “Music Key” service is more about pacifying major labels.

“Fundamentally, Google gets everything it needs from the music business out of YouTube as it is at the moment, so doing this new paid service is mainly about doing it because the labels are pushing them to do it, and that’s how they protect the relationships for the core business, which is YouTube,” he says.

“Google is saying ‘okay, we’ll do you a thing, we’ll put a bit of effort into it. But when you see the scale of Google, where they do $9bn-$10bn acquisitions, the money they’ve put into this has been very small,” he continues.

“They can get a music service out there that keeps the big labels on board, but Google is very good at killing things off very quickly. I wouldn’t be surprised if they do this, and then two years down the line say ‘oh, we’re killing this, we tried but it didn’t work…’.”

Fear for Spotify’s future

What happens to Spotify in a world where Apple could suddenly bundle Beats Music into tens of millions of new iOS devices, and where Google has YouTube – whether or not its paid subscription version takes off?

Spotify is the most successful streaming music service for paying customers with its 10m subscribers, and there has been speculation that it may go public in autumn this year.

Mulligan thinks there is more riding on the latter ambition than people realise, pointing out that there hasn’t yet been a big “exit” for a streaming music company that relies on striking direct licensing deals with labels and publishers.

This rules out Pandora (which went public in 2011) and Last.fm (which sold to CBS for $280m in 2007) because they used “statutory” licences that didn’t require direct negotiations with labels. And he discounts Beats Music because “it wasn’t the reason Apple paid $3bn for Beats, even if it helped the deal go through”.

Why does it matter if Spotify can or can’t go public or be bought for billions of dollars? “If Spotify can’t have a big exit, the doubts that are already there around digital music could become potentially fatal,” he says, noting that other digital entertainment areas, like mobile games, have seen plenty of such exits.

“We need Spotify to be a success for there to be capital flowing back into this space from investors. If it can’t, it raises really big questions about who is going to invest in a standalone digital music company at scale.”

Artists aren’t out of the woods

Finally, what does this transition from sales to streams mean for artists: the songwriters and musicians who make the music being streamed on Spotify, YouTube, Beats Music and other services?

The basics are clear: streaming services pay money to labels, publishers and collecting societies, who pass that on to musicians according to the terms of their contracts.

How the initial payouts are calculated is sometimes clear and sometimes not: Spotify pays 70% of its revenues out and launched a website to explain the process, while YouTube is famous for its non disclosure agreements (NDAs).

How the money is then passed on to songwriters and artists? Well, that’s another murky can of worms entirely. Musicians’ complaints about their streaming income aren’t just about low royalty cheques, but also about the music industry’s ignoble history of artists getting screwed whenever there’s a big format change.

Is the current transition bad news for artists? Mulligan doesn’t mince his words. “Artists are going to feel pain for at least another four to five years, just as they did in the first four to five years after iTunes launched,” he says.

“But the story there is that artists came out the other side: very few artists would do anything other than consider iTunes royalty payments have been a fundamentally important part of their income.”

He thinks that when more than 100m people are paying to stream music, the picture will be much brighter for artists, but notes that “with probably 37m subscribers globally by the end of this year, it’s not at the end of 2014 or even 2015 that artists are going to suddenly say ‘yes, streaming makes sense to me now’.”

“They will all see significantly less money coming from downloads and CDs over that time though. It’s going to be a painful year or two for the average musician. And it may be harder for the people in the music world before this change to adapt than it is for artists born into this world,” he says.

A new generation adapting

Mulligan, who is a musician himself, sees a new generation of artists and managers growing up with streaming, and figuring out how to forge sustainable careers through it.

“If you’ve got a fanbase of 30,000 fans, and 10 years ago you could have relied on half of them to buy your album, maybe now that’s 10%, but 50% to 70% will stream your music,” he says.

“That’s a larger number of them engaging with you directly, and you’ve got more chance of getting them to do other stuff, which is going to be key when you think about how an artist makes up this shortfall [from sales] over the next two to three years.”

Mulligan doesn’t dodge the question about whether some artists and smaller labels will survive this tough period, suggesting that there will be “collateral damage” of those who find it difficult to adapt. He’s optimistic about newer artists though.

“Nowadays, as an artist you’re less likely to get signed until you’ve done a couple of years do-it-yourself to prove you have an audience. And if an artist has spent two years doing that, they’ll have a much clearer idea about all these changes,” he says.

“There’s a generation of artists who are essentially having to behave like mini-labels themselves in their early career. They’re going to be much better equipped to forge sustainable careers out of music, particularly compared to artists from the 1990s.”

• Seven reasons Google might buy Spotify

• Apple iTunes exec: ‘Creatively, we really believe in albums’

• Why YouTube might block indie labels

• Five big challenges looming for streaming music services