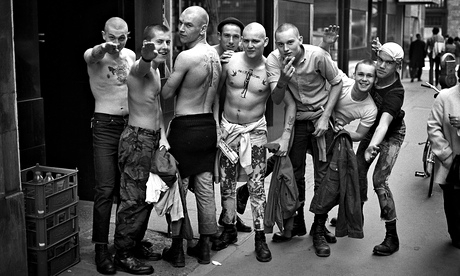

If you are old enough to remember London in the late 1970s and early 1980s, Derek Ridgers' new book Skinheads 1979-1984 is a reminder of the latent aggression that defined youth culture in the capital, and sometimes made the journey home by night bus and tube train a risky business.

On the street, skinheads, who always seemed to travel in packs, were a threatening presence. At gigs, especially during the 2-Tone era, they were disruptive going on violent, often making the dancefloor at shows by the Specials, Madness and the Selecter a place where you had to watch your step even as the music urged you to do otherwise.

Then there was the racism and the fascism, the storming of shows by the Redskins, and the attempted disruption of anti-fascist marches or anti-racist festivals. It was a different country back then: harder, more tribally and politically polarised. Ridgers' images show the skinheads of the time living up to their reputation – Nazi salutes, swastika T-shirts, tattoos, armbands and White Power insignia – but he also captures the mostly male camaraderie of belonging that drew young, mostly white, working class males into the fold. (There are a few photographs of young black men who embraced skinhead culture here, but they tended to belong to the more style-conscious tribe that also congregated around 2-Tone, taking their sartorial cue from the original post-Mod skinhead era of the late-60s, where attention to detail – Crombie, Ben Sherman, cropped jeans, brogues, red socks and matching handkerchief – was all.)

The most arresting mages here are the most disturbing: ultra-racist skinheads with tattooed faces, foreheads – Made In England is one unequivocal stamp of allegiance, but surely Made In Sligo is asking for trouble? – and fascist T-shirts. This is the lumpen, angry skinhead of your worst nightmares, the sort of lads that used to congregate around the Bethnal Green Road end of pre-hipsterised Brick Lane selling National Front newspapers and shouting abuse at the local Bangladeshis.

More intriguing, though, are the prettier boys whose soft gazes seem to contradict the very ethos of skinhead culture. An angelic-looking lad has the words "We are the flowers in your dustbin" – a Sex Pistols' lyric – tattooed across his forehead. Jean Genet, you feel, would approve.

The skinhead girls, so often portrayed as simply an addendum to this most ultra-male of all youth cults, also come into their own: the feather cuts, chunky cardigans, polished brogues, bleached denims and braces. Often, for all their posturing, they look cute. One of them could pass for a model in a style shoot about retro youth cults, her elfin beauty only emphasised by her closely cropped hair and utilitarian clothes.

"I thought they were the most photogenic youth cult of all," writes Ridgers. "Among them were some undeniably beautiful and memorable faces, some of the best faces I've ever photographed."

For all the pared-down machismo of the look, skinhead was also, when adhered to with a meticulousness that denotes latent obsession, a kind of ultra-minimalist style statement with its roots in the mid-60s' confluence of Mod and Jamaican rude boy culture. As style commentator Josh Simms writes in his introduction to this photobook, Ridgers' street portrait of a skinhead couple on London's Brick Lane in 1980 "reveals just what a carefully assemblaged style it was, however utilitarian, accessible and 'man of the people' its components".

As I have noted before, Ridgers is the foremost visual documenter of London's style culture from the early 1970s until the present day and Skinheads 1979-1984, like his recent photo-book, London Youth 78-87, is another glimpse of his vast archive. It is a less formal, more photojournalistic, book, wherein portraits are mixed with street reportage of skinheads at rest and at play – though the latter usually tends towards the fomenting of trouble as Ridgers' series of skinheads gathering at Southend for the Easter bank holiday in 1979 attests. Trouble hovers in almost every shot.

For all that, there are many shots of skinheads lounging around, doing nothing, bored and enervated. This, too, is a sign of those now distant times: no jobs, no money, no future – the Britain that punk summoned up and railed against was a Britain that skinheads knew all too well, their embrace of extreme nationalism a kind of warped reflection of their acute sense of not-belonging. "When I first ran into skinheads in 1979," Ridgers writes, "I had no absolutely idea of how profoundly resentful they felt about their lot."

Perhaps the most revealing section in his anecdotal essay concerns the first time he exhibited a selection of these photographs in 1980 in an art gallery in Chelsea. Simply called Skinheads, the show caused quite a stir in the media and among the public who flocked to see it. "The exhibition certainly seemed to strike a chord," Ridgers recalls. "Most of the comments in the visitors' book were favourable, but a couple asked why I'd only interviewed those skinheads with very extremist views? That wasn't the case at all. Those were the only views I heard."

• Derek Ridgers' Skinheads 1979-1984 is published by Omnibus Press at £14.95. Buy it for £11.96 with free UK p&p at guardianbookshop.co.uk