Living as I do in New York City, I’m frequently quizzed by relatives and out-of-town guests about “what shows to see”. While I do enjoy plays, there are few things I’d rather do less than shell out $150 to see a modern tourist-friendly Broadway musical. To spare myself humiliation, I lie and tell people to go see Wicked. (I’ve never seen Wicked.)

So it was against all my defensive grumblings when I went to see the Jay Z and Will Smith co-produced Fela! On Broadway musical a few years back. My only regret is that I only saw the show once.

Documentarian Alex Gibney (Taxi to the Dark Side, Client 9: The Rise and Fall of Elliot Spitzer) uses this recent production as a framing device to tell the story of Fela Ransome Kuti, the pioneering forefather of Afrobeat, who died in 1997 at the age of 58. While not exactly a stylish film (one can catch this very straightforward doc on VOD or home video without fear of missing anything) Finding Fela is certainly thorough. Without underselling his musical achievements, Kuti’s life as a political dissident in Nigeria is a fascinating microcosm of post-colonialism. But political movements always go down smoother when they have a danceable beat.

Kuti was born to an influential family. His father was a school headmaster and Protestant minister. His mother was a trailblazer for women’s rights in Africa. His older brother attended medical school in the UK, but Fela and studying never quite connected. He was drawn to music and basically created his own genre when he took elements from local dance music (known as Highlife) and mixed it with jazz (Kuti could wail on the sax) and the tightly disciplined soul of James Brown.

He discovered this third element during a 1969 trip to Los Angeles, in which he also encountered the Black Power movement. He then returned to Nigeria, formed his legendary band Africa ‘70, and produced an enormous amount of material, including many deep groove jams that lasted entire album sides. He built his own club (the Shrine), where he’d perform his lengthy, high energy sets, complete with dancing girls and political raps.

In time, Fela had so large of an entourage that he build his own compound. He declared his little parcel of land in Lagos to be its own sovereign nation, the Kalakuta Republic – which probably wasn’t the smartest thing to do. His lyrics were already defiant toward military leaders working closely with foreign oil companies, and since the government had just concluded a lengthy civil war with the breakaway state of Biafra, they eventually brought the hammer down hard.

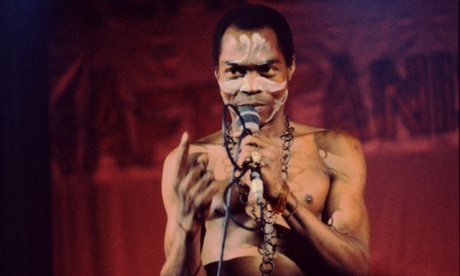

Naturally, this merely made Fela more dedicated to the struggle. It also made him more of, as they say, a character. Most of the primary footage of him shows him perennially naked except for tight, short colorful underwear. His second band, Egypt ‘80, took on an even headier direction, blazing through circular jams that were as infectious as they were unprogrammable on radio.

Despite being married and having children, he kept a harem of mistresses – later marrying dozens of them in a ceremony he claimed brought him back to tribal roots. He also employed an odd Ghanaian gentleman as a spiritual guide who went by the name of “Professor Hindu”. His head soon swirled with stories of transcendent powers that could cure disease, alter his physical form, and make money seem invisible to customs agents. (It should be added that there was also a great deal of marijuana being passed around.)

Gibney has all this material down and makes good use of Broadway director Bill T Jones’ struggles to tell the story as a mirror for modern contextualization. (Admittedly it does teeter on the edge of seeming like an advertisement to buy tickets for the show, but the New York run has already closed.) These sequences are mixed with talking head interviews with Fela’s children, which are especially effective when detailing government harassment and prison beatings, as well as footage from Jean-Jacques Flori and Stéphane Tchalgadjieff’s 1982 documentary Music Is The Weapon.

Finding Fela does an exemplary job of explaining, in musical terms, what made Fela standout, a simple enough step that most music documentaries ignore. Fela himself is a vexing figure. Whether you feel he should be canonized as a freedom fighter or dismissed as an egomaniac is left a little bit open ended.

Considering the length of a typical Fela song, we don’t actually hear a full one during the performance, so one could argue that the frequent track-switching leads to a blur in which much of the material sounds similar. But knowing Fela’s position that his music be seen more as a driving political force than as a series of tunes, I don’t think he’d get too worked over accusations that he played one long song.

Finding Fela is out 1 August in New York and will be released in the UK on 5 September

• This article was amended on 31 July 2014 to clarify that Fela’s spiritual adviser was known as “Professor Hindu”, not “Doctor Hindu”, and that he was Ghanaian. This article was also amended to correct the spelling of the Kalakuta Republic, from Kalkatua Republic as an earlier version said.