It's one thing to discover a new talent, quite another to rediscover an old talent. The two experiences offer different satisfactions. The former involves the capacity to recognise and create fashion. The latter offers the pleasures of defying changing fashions, of restoring and confirming old hopes, beliefs and enthusiasms, of seeing justice done and traditions confirmed. One thinks of Bill Russell in the 1940s tracking down the New Orleans jazz men Bunk Johnson and George Lewis working in Louisiana cane fields, getting their instruments out of hock and recording new versions of their work. Of the novelists Jean Rhys in England and Henry Roth in the US, whom many thought dead, being found in rural retreats and brought back into print. There is something rather like this in the remarkable, if at times somewhat dubious, documentary Searching for Sugar Man.

Since the 1970s two South Africans, the record shop manager Stephen Segerman and the music journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, have been fascinated by the Detroit-based folk-rock singer Sixto Rodriguez, through two LPs he'd recorded in 1970 and 71, Cold Fact and Coming From Reality. They'd made little impact in the US but, initially through bootleg versions, they'd had an immense impact in South Africa. Their eloquent attacks on prejudice, injustice and suppression appealed to young white liberals who saw in them themes inspired by the troubles and traumas of the American 1960s that were applicable to their own defiance of apartheid. Rodriguez became bigger there than the Stones or Elvis, his records outsold Abbey Road, and apparently copies of his LPs had particularly provocative tracks scratched to make them unplayable on the radio.

The pair knew no more about the singer than they found on the record sleeves, where he appeared simply under his family name, though the songs were attributed to Sixto or Jesus Rodriguez. He'd become a legend in South Africa but a rumour circulated that he was dead, possibly dying mid-performance after singing a bitter song with the valedictory lines "But thanks for your time/ Then you can thank me for mine/ And after that's said, forget it."

In an increasingly less haphazard way, Bartholomew-Strydom and Segerman set about tracking him down, and their search was eventually rewarded in 1998. Some years later, Malik Bendjelloul, a documentarist making films on rock musicians for Swedish television, met the South African questors in Cape Town and determined to make a film of their obsessive pursuit. He considered it offered unique insights into the history of popular music, the vagaries of the rock scene and the nature of celebrity in our time.

Wanting to make something on a larger scale than his half-hour TV programme, he came into contact with two of Britain's most ambitious producers of big-screen documentaries, Simon Chinn, whose credits include Man on Wire and Project Nim, and John Battsek, who made One Day in September (about the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre) and Restrepo (one of the best films on the Afghanistan war). They shared Bendjelloul's enthusiasm, and the result is a fascinating movie that reflects the different talents of this five-man team.

Some people believe that references to the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima in a review of Clint Eastwood's Flags of Our Fathers or the revelation by a movie critic that HM Stanley met David Livingstone in the film that bears their names constitute unforgivable "spoilers". If you're one of them, stop reading this column instantly. Because, after a deep breath, I must reveal that the makers have constructed their picture in a teasing way around the idea of the hunt for Rodriguez, using interviews with those who worked with him in the music business, laboured alongside him on building sites or served him beer in Detroit. There are artful animated scenes, atmospherically setting up the crumbling city he lived in and suggestions that he was an elusive, shadowy figure.

Eventually he turns up alive and well via information from his daughters and a reference to Dearborn (Michigan hometown of Henry Ford and his organisation of which Rodriguez's pursuers have seemingly never heard). He's presented as a recluse, reluctantly revealing himself at the window of the run-down house he's inhabited for 40 years.

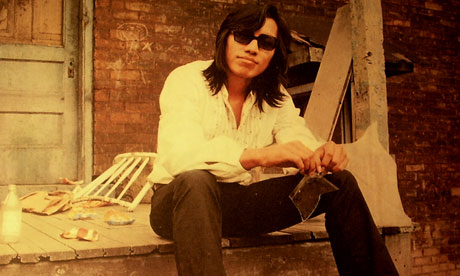

This is all fascinating but rather misleading. The striking-looking son of immigrant Mexican parentage, Rodriguez is no simple introvert. Born in Detroit 70 years ago this summer, he has the brooding look of Geronimo. He grew up singing in bars, took on manual work to give his three daughters an education, graduated in philosophy in the early 1980s and stood unsuccessfully for elective office on a left-wing ticket. The movie makes a great deal of his popularity in South Africa and the fact that he was amazed by his reputation there and even more so by the reception during a tour in 1998. But it doesn't mention his parallel following in Australia and New Zealand and his tours there in the 1970s, nor his visits to Sweden and his British appearances in recent years.

There are many things we'd like to know about Rodriguez and his background. I'd be interested to hear more about what happened to the royalties sent by his South African publishers that never reached him, though there is a wonderfully evasive interview with the former director of a Detroit record company now living beneath the Hollywood sign in Los Angeles. But it's a revealing tale of showbusiness and its operations, of how someone could disappear almost without trace in a world where everything appears to be known and all information is available at the speed of a mouse.

What makes it particularly intriguing is that the end is happy without being triumphalist. This modest, talented man didn't become a star and has been turned into one by rediscovery. But he seems to have had a fulfilling life in one of America's least welcoming rust-belt cities.