After a handful of writers happened to publish novels that depicted Henry James as a character, or paid homage to his work, David Lodge – who was one of them – christened 2004 "the year of James". In the same spirit, it could be said that this is the summer of Eric Rohmer. Some of the season's most prominent films, including Frances Ha, Before Midnight, and Exhibition (which recently opened the Locarno film festival), show the influence of the French director, who died in 2010, and whose lithe and playful work extended the possibilities of a certain kind of small-scale, psychologically curious, dialogue-led drama.

Though Rohmer's name has been invoked whenever films include anything other than exploding fireballs and blood-drenched zombies, it's not hard to see his influence on the current crop of films – with their analytical men and "thin and delicate girls" (a description from 1970's Claire's Knee); their dialogues about love, morality or painting; their non-professional actors; their gentle irony and anecdotal narratives.

One director who happily admits the influence is Noah Baumbach, director of The Squid and the Whale, Greenberg and most recently Frances Ha. Baumbach was in his late 20s and already directing by the time he recognised Rohmer's appeal during a 1999 New York retrospective. But he got "so into" Rohmer's world, he says, "that when Pauline at the Beach accidentally arrived at the movie theatre without subtitles, I stayed anyway and understood it". (Since then, Baumbach's infatuation has grown to the point that he has named his own son Rohmer.)

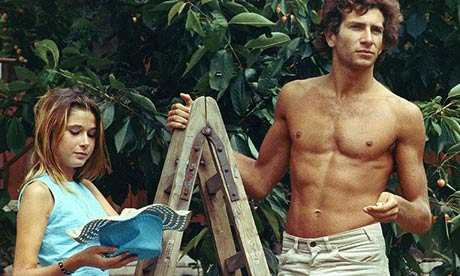

Though Quentin Tarantino once referred to the cliche of the "Rohmer genre"– talky, uneventful, French – in fact the films fall into two distinct subgenres, represented by his two main film cycles, the Moral Tales and the Comedies and Proverbs. The earlier sequence – two shorts and four features, including My Night with Maud and Claire's Knee, made between 1962 and 1972 – consists of spare dramas, often using voiceover and told from the perspective of a man, either married or committed, who is tempted to stray. The six films in the Comedies and Proverbs series (1981 to 1987), among them Pauline at the Beach, Full Moon in Paris, and Le Rayon Vert, are romances or would-be romances, employing multiple, mostly female perspectives, making extensive use of coincidence and complication, and ending, if not on an upbeat note, then in an atmosphere of acceptance and accommodation. Different though they are, what the two sequences share is a putatively casual approach to narrative, and an unabashed minimalism – simple set-ups, next to no music.

Mia Hansen-Løve, who made last year's bittersweet romance Goodbye, First Love, grew up watching Rohmer's films on TV with her parents – "my mother identifying with the characters, my father making jokes" – and spent her holidays in Dinard, where Rohmer filmed A Summer's Tale, in which a young man on holiday becomes caught between three women. As an aspiring film-maker, she found his work "helpful and encouraging", she says.

"I'm not saying that without Rohmer, no one would have thought to make long dialogue scenes," she adds. But he defied the cliche that "the less people talk, the deeper you can go – that talking is theatre, and film-making is action. He said that, for him, the character was only really alive once they were actually talking."

It isn't just Rohmer's style, says British director Joanna Hogg. She envies above all his "consistency of career. He carried on working in his own way, at the scale that suited his films."

For his part, Baumbach is struck by the simplicity of Rohmer's technique: "Sometimes it feels like he isn't doing anything," he says. "That's probably the hardest thing to accomplish in movie-making."

Though Baumbach claims not to know how his love of Rohmer has affected his recent work, it's hard to deny that Frances Ha – a 27-year-old dancer, emotionally restless and struggling to find a groove – recalls Rohmer's own portrait of a single woman's abortive holidaymaking, Le Rayon Vert. The resemblance makes itself even clearer when Frances visits Paris, a trip she spends sleeping, glumly reading Proust and talking to the voicemail service of a friend of hers who lives there.

While there is no question that Rohmer has had an impact on these directors' work, what they aspire to emulate is how successfully he realised his own possibilities. Hansen-Løve says she never asks herself how he would approach a particular scene: there's no point. "It makes no sense to try to be a 'new Rohmer', because Rohmer was not a 'new somebody'," she says. "That was why he was great."