What was once anecdote has become quantified theorem: rap is the most influential form of American music of the last 50 years. According to a new study called The Evolution of Popular Music: 1960-2010, we can now mathematically prove that hip-hop carried more clout than rock.

For someone like me, a nerd – I mean a scholar who has studied, taught and written about rap music for the last 20 years – this moment presents something of a vindication.

I can remember vividly the chuckles and outright laughter that I received as a budding Ivy League scholar when explaining why I wanted to study hip hop music. In the early 1990s – which, according to Matthias Mauch et al’s study was the very moment rap music established its indelible impact on popular music – I was often challenged by academicians on the limited impact that rap music could make.

Some doubted the viability of studying something that was for many – even in the 1990s – simply a fad, a form of music that wasn’t really music. But I knew then what I know now: rap music is here to stay.

The qualitative evidence of this fact has been obvious to me for at least 20 of the last 40 years. But this study does more than just vindicate those of us who study rap music in the academy: it also validates the extraordinary cultural influence of what Bakari Kitwana has defined as the hip-hop generation: those of us born between the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s who have been wrestling with the rise of neoliberalism, the consequences of the prison-industrial complex and the withering effects of globalisation in the post-civil rights era. That struggle has, to some extent at least, has been articulated through rap music itself.

The key piece of information “discovered” by Mauch et al is that there were three major influential shifts in popular music in that 50-year period. One, in 1964, related to the decline of popular jazz/blues forms and the rise of rock music; one in 1983, reflected the emergence of pop/stadium rock; the final, most pronounced shift came in 1991, with the popular emergence of rap music. This final shift falls within the period known to scholars of hip-hop culture as the Golden Era.

The Golden Era was the moment where Public Enemy and the Native Tongues clique – which included A Tribe Called Quest, The Jungle Brothers, Queen Latifah and De La Soul – were making music that was nearly as popular as that made by NWA (Niggaz With Attitude), Ice-T, the Wu-Tang Clan and eventually Dr Dre, Snoop Dogg and Ice Cube.

It was a moment of relative diversity within hip-hop music. Songs about fighting oppressive power structures could be as popular as songs that deliberately degraded women. Rap music met the information age, producing some of the form’s most potent results.

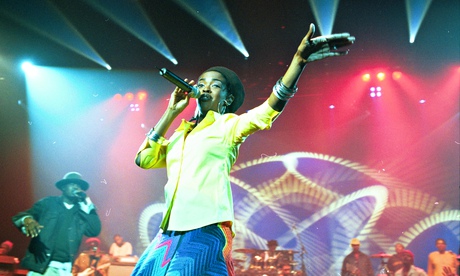

In many ways rap music was made for visual consumption. So while video killed the pop radio music star, it simultaneously gave birth to the rap star. Rappers relied (and continue to rely on) visual communication to appeal to audiences hungry for narratives that represent urban black experiences.

Several rap legends – major figures in the music and culture such as Nas, Lauryn Hill, Biggie Smalls, and Tupac Shakur - emerged during the early days of the Golden Era when video ruled the waves.

The Golden Era of rap also represents a marked shift in the music’s lyrical content. At the end of the 1980s Public Enemy, one of hip-hop’s most political rap groups, was signed to Def Jam, a mainstream major label. The subsequent album, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, was (and is still) considered a hip-hop classic.

At the dawn of the next decade, however, NWA had supplanted Public Enemy with a brand of hip-hop that featured gangster narratives of materialism and misogyny. The lyrical landscape of rap music had altered irrevocably.

The Golden Era also signalled the music industry’s somewhat late acknowledgement of the economic viability of rap music. Rap, it turned out, could pay – which in turn produced the kind of formulaic musical mass production that all too often characterises pop culture.

But don’t give up hope. A quick listen to Kendrick Lamar’s recent masterpiece To Pimp A Butterfly proves Mauch’s thesis that “[t]he rise of rap and related genres appears … to be the single most important event that has shaped the musical structure of the American charts.”

To Pimp A Butterfly is a cornucopia of black musical styles and sounds. It references jazz as readily as it does funk, spoken word and black soul music. It puts into bold relief many of the reasons why rap music matters so much to so many of us. Rap music is a living, breathing repository of black musical genius. And as such, its cultural and musical prominence is here to stay.