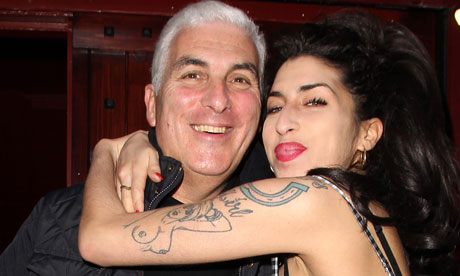

The extraordinarily talented Amy Winehouse died on 23 July 2011. Dedicating this book to her and his parents, Winehouse's father, Mitch, writes: "Love transcends even death." There follows what amounts to a love letter to their close-knit Jewish London family, their shared love of jazz, and Amy in all her manifestations: the mischievous child and disruptive schoolgirl; the multimillion-selling, award-winning songbird of Frank and Back to Black; the bedraggled junkie-outlaw, pursued by paparazzi through dark streets, in her bloodied ballerina pumps.

In the end, it was alcohol that killed Amy, but, if this book illustrates anything, it's how desperately tedious the life of a drug addict is. Amy started out chanting "Class A drugs are for mugs". Later, in the grip of her addictions, she would perform blitzed, mess up golden opportunities, and make doomed attempts at rehab. As with many addicts, self-awareness wasn't her strong suit. Mitch wryly recalls the time Amy told him she didn't want a perfume licensed in her name. "'I don't want to hurt my credibility,' she told me, as she sat there high on crack."

In a shocking twist, Amy's last boyfriend has recently been charged with rape. However, the "baddie" of Mitch's tale is her former husband, Blake Fielder-Civil, who introduced her to drugs. Blake is portrayed as a Camden Market "Bill Sykes" to Amy's besotted "Nancy". Mitch hates that the song Back to Black is about Blake, but then reasons: "Nobody's going to have a chart-topping album full of songs about someone's good deeds." Throughout the book, his loathing for "Blakey" seeps through the pages like a dark stain.

As for the author, Mitch is quick to point out that proceeds from this book will go to his daughter's foundation. There are times when Mitch seems just a tad over-involved in his daughter's life (Blake's parents dub him "The Fat Controller"). Other times, he seems dazzled by the showbiz lights. However, mainly Mitch comes across as distraught and exhausted, juggling the myriad roles thrust upon him by Amy's condition: minder, carer, protector, shrink, troubleshooter. After yet another round of secrets, lies, drama and upset, Mitch observes: "Never mind my daughter swanning around the Caribbean: I needed a holiday – from her.".

Analysis of Amy's cultural impact is scant. This is a literary torch song, about a parent looking on in impotent agony as their child self-destructs. Take away Amy's transcendent talent, and a comparable book would be Deborah Spungen's And I Don't Want to Live This Life, about her daughter Nancy, the murdered girlfriend of Sid Vicious. With Mitch's book, there is the problem of deja vu (many of these stories have already been aired). However, he does a fine job of fleshing out his daughter, in all her contradictory glory: the exhibitionist with stage fright; the broken doll with the soft centre; the wild child who yearned for motherhood; the hopeless romantic who loved too much, and cared about herself too little.

The manner of Amy's passing proves that a death can be half-expected but still devastating. One is left wondering, was she a victim of her own mythology? How could such potential turn to ashes in her hands? But such questions shrivel into insignificance in the reality of addiction.

After his daughter's death, Mitch rather poignantly sees "signs" from Amy in butterflies and birds. If parenthood is an emotional rollercoaster, he is still hanging on.