Reggae fans didn't need to go to Jamaica to hear the best music in the 1970s and 1980s. They didn't even have to live in big cities such as London or Birmingham. In Huddersfield, West Yorkshire – the hometown of Harold Wilson – it was once possible to see international stars performing live at the West Indian Club on Venn Street, or skank the night away to one of 30 or so sound systems from the town.

"Gregory Isaacs, Burning Spear, Jimmy Cliff, Sugar Minott, Desmond Dekker … everybody played at Venn Street," remembers Claston Brooks, aka Danman, who ended up getting a job at the West Indian Club so he could see the gigs for free. "The artists might do one other show in Birmingham or London, but more often than not they would come from Jamaica direct to Huddersfield. They'd stay at the George Hotel, which is still there, play their show and boom, back to Jamaica. Sound systems would come over from Kingston to play Venn Street. That's how big it was."

The influence of sound systems on British music, from trip-hop to dubstep, is well documented. However, Huddersfield's role in this culture has been largely overlooked. Now, a new book is paying overdue tribute to the town's achievements. Part of a heritage project put together by historian Mandeep Samra, Sound System Culture: Celebrating Huddersfield's Sound Systems, compiled by Al Fingers, is filled with beautiful archive photography and includes a detailed written history of the scene.

"Artists would come to Huddersfield because people were friendlier and more broad-minded than in many areas of Britain in the 1970s," explains Paul Huxtable, builder and operator of the Axis sound system, who wrote the main text of the book. "People would say to [reggae superstar] Dennis Brown: 'We're having a christening tomorrow. Why don't you come along?' I heard of people putting stars up at their houses. You didn't get that in the cities. Every town with a large black community had a sound system scene, but Huddersfield's was vastly out of proportion to the size of the place."

Reggae sound systems are mobile discos on which selectors (DJs) play popular records on huge speakers, with vocal accompaniment known as "toasting" provided by deejays (MCs). They originated in Jamaica in the 1950s and were brought to Huddersfield in the 1960s, when the first wave of Caribbean immigrants arrived to work in the town's textile mills.

The first sound systems in Huddersfield were simple affairs, playing rocksteady records at all-night "blues parties" held in people's houses. Then a younger generation began using a similar template to play heavier dub and reggae tunes.

As the first black boy to be born in the town's Princess Royal hospital, Stephen "Papa Burky" Burke of the Earth Rocker sound system found himself at the vanguard of this changing culture. "I built my first boxes [speaker cabinets] out of cardboard when I was 16," he says. "It sounded brilliant in my bedroom, but when I took it into a bigger hall the amplifier started smoking. I realised there was a bit more to it …"

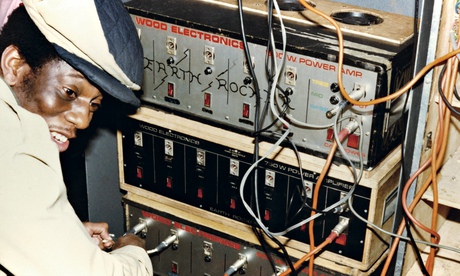

The sound systems that evolved were complex feats of engineering. Because commercially available speakers were prohibitively expensive and could not provide the bass needed to fill a large venue, kids such as Burke learned joinery in order to build their own. Then came the electronics. Earth Rocker's electrical work was carried out by local man Pete "Woody" Wood, who went on to work with Ultravox and a number of other 1980s bands.

However, other sound systems were less professional. Brooks is full of tales of system builders stealing wood from timber yards or loudspeakers from garage forecourts. He even claims to have forgone wearing underpants and socks to save the cash for electrical cables. "To get big you need to build," he says. "Once you're big enough, you don't need to do dem things."

The rush to keep ahead of rival sounds systems often meant driving in the dead of night to Nottingham, where the latest Jamaican reggae imports or pre-releases were exchanged at clandestine meetings held in car parks. Once they were safely back home, the sound system operators would scribble over the record labels with marker pens so their competitors would not be able to see what they were playing.

"It was all about having the freshest records and the biggest sound," says Huxtable. "So they'd have echo chambers, syn-drums, wardrobe-sized cabinets with 18in drivers. Everything was geared to getting the maximum power from the amplifiers. Reggae sound systems always run in the red, so things have to be highly engineered so you don't burn things out."

Although every system sounded different, a common link could be found in shape of the Matamp. Hans Alfred "Mat" Mathias was a Holocaust refugee who started an electronics shop on King Street. Eventually, he found himself hand-building amplifiers for the local sounds, who preferred valve systems to transistors because of the warmer bass they produce. Pictured in the book, wearing a crisp white shirt and tie, Mathias looks more lab technician than reggae man, but his company became internationally renowned.

"Mat was a German Jewish man making amplifiers for West Indians in Yorkshire," says Ian Smith, whose band the Inner Mind recorded in a tiny studio that Mathias operated near his shop. "You couldn't make it up. He sold chocolate, cigarettes and amplifiers."

A white man, whose reggae band were happily accepted in Caribbean clubs, Smith typifies the era's cheery openness. Although racism did exist in Huddersfield, anyone – black, white or Asian – was welcome in clubs such as Venn Street and Arawak. The reggae clubs even accepted punk bands: Burke remembers curiously venturing in to see Adam and the Ants at Venn Street.

As the scene expanded, shops including Steve's Records and Music City sprung up. Local band Jab Jab provided backing for Dave & Ansell Collins on Top of the Pops in 1971, when the Jamaican duo reached No 1 with the classic Double Barrel. When another Huddersfield group, the Groovers, recorded a cover version of Bob Marley's Bend Down Low during a trip to London, the man himself paid them a visit in the studio.

But, for many young black men, sound system culture provided something deeper than entertainment or the chance of financial success. It offered empowerment, education and a voice.

"With a sound system and a microphone, you can become a history teacher," says Armagideon's Donovan Brown aka D.Bo General. "You can tell people things that aren't on the television. It's about identifying yourself and waking people up to what they can achieve."

Today, there is little left of this vibrant scene. Venn Street was demolished in 1992 to make way for a car park, and more sound systems faded away with the closure of other key venues.

However, Huxtable has recently shipped a custom-built valve system from his Huddersfield workshop to Jamaica. Meanwhile, some of the scene's originators are stringing up their speakers once again.

"When Gregory Isaacs played in Venn Street supported by a sound system, so many girls fainted that they had to call ambulances," says Brooks, who now performs as an MC for the Leeds-based Iration Steppas. "When that club closed, it was like part of Huddersfield had died. If I had a piece of land, I'd build it up again."

• Sound System Culture – Celebrating Huddersfield's Sound Systems is published by One Love Books.